Police investigations and criminal trials are, in an ideal world, intended to discover the truth, identify the guilty, and exonerate the innocent. Unfortunately, the world we live in is far from ideal, and investigations and trials are conducted by human beings who are vulnerable to error, prejudice and, at times, outright corruption. Sometimes, despite the sincere best efforts of everyone involved, mistakes are made and a wrongful conviction occurs. Other times, as in the case of Barry Gibbs of New York, something more sinister is at work. Mr. Gibbs served 17 years of a second-degree murder sentence before it was discovered that the investigating detective had framed him to cover up a Mafia-related killing.

The story of Gibbs’ wrongful conviction began in 1986. At that time Gibbs, a Navy veteran and a postal worker, was accused of murdering Virginia Robertson. Ms. Robertson was found strangled to death on November 4th, 1986, her body dumped near the Belt Parkway and covered with a blanket. A jogger witnessed the dumping of the body, reporting initially that he had seen a Caucasian man, about 5’6” and 140 pounds, removing the body from a gray car. Although Mr. Gibbs was substantially taller and heavier than this description, the witness picked him out of a police lineup and later identified him on the witness stand. That jogger, David Mitchell, later admitted that he had been forced to lie by the investigating detective, Louis Eppolito, who had threatened his family.

Coercing an eyewitness was not the only way in which Eppolito molded the evidence to point to Mr. Gibbs. The killer had been seen wearing a pair of red jeans, and a similar pair turned up in a search of Gibbs’ residence – though they did not fit him. Gibbs owned a gray car, but it had long been inoperable with two flat tires. A police informant who was incarcerated with Mr. Gibbs before trial claimed that Gibbs had admitted to the murder, though other witnesses who were imprisoned with Gibbs asserted that Gibbs maintained his claims of innocence throughout his incarceration. Mr. Gibbs has also claimed in the civil rights lawsuit he filed after his eventual exoneration that Eppolito withheld evidence from prosecutors that would have exonerated Gibbs, and that Eppolito beat him until he gave a false confession. On the strength of this and other fabricated evidence, Mr. Gibbs was convicted of second-degree murder in 1988.

A break in Mr. Gibbs’ case finally came in 2005, when the former detective, Eppolito, and his partner Stephen Caracappa, were indicted for crimes committed in connection with their ties to the Luchese crime family, including passing along documents and information about police investigations and participating in Mafia killings or covering them up. An attorney working with The Innocence Project, an organization that works to help the wrongfully convicted clear their names, recognized Eppolito as the investigating detective in Gibbs’ case and pushed for a federal investigation. A search of Eppolito’s Las Vegas home turned up Gibbs’ case file, which was missing from police records. The case against Barry Gibbs began to unravel as the extent of Eppolito’s corruption was revealed.

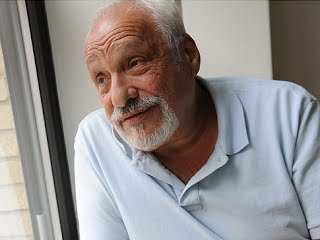

Barry Gibbs was finally exonerated and released from prison in September of 2005, after serving 17 years of his sentence, plus the two years he spent in prison awaiting trial. The world had changed dramatically in nearly two decades, forcing Mr. Gibbs to adapt to computers, cell phones, and countless other changes in technology and society. With his attorney’s help, he sued the City of New York for the violation of his rights and his wrongful conviction and incarceration. A settlement was reached, and in 2010 the City agreed to pay Gibbs $9.9 million. That strikes most people as a huge sum of money, but serving almost 20 years in prison for a crime he did not commit exacted a high toll on Mr. Gibbs, leaving him with lasting emotional scars. A corrupt police officer robbed Gibbs of almost two decades of his life and branded him a murderer. Though the system did eventually work to correct its error, without the efforts of private organizations like The Innocence Project, Mr. Gibbs would still be behind bars.

The case of Barry Gibbs illustrates how helpless an innocent person is in the face of a justice system that has already decided their guilt (or has reasons to make them appear guilty). Only because Mr. Gibbs had access to the help of experienced legal professionals was he eventually able to clear his name. A good defense attorney has access to resources and connections that private individuals lack, and understands the law and police procedure. Not all police are Louis Eppolito, but even honest mistakes can lead to a wrongful conviction. You deserve the protection of experienced legal representation. That representation must start as early in the process as possible. If Mr. Esposito had the resources to retain aggressive, skilled criminal defense counsel form the outset, his case and life might have been very different.

Leave A Comment